Accessibility is not an afterthought

Most people in the tech industry have heard of web accessibility, but far fewer people feel confident they understand.

That uncertainty has led to a handful of persistent misconceptions that tend to shape how teams approach accessibility—often in ways that make it feel bigger, harder, or more expensive than it needs to be. Let’s debunk those myths:

- Myth #1: Web accessibility compliance is a lot of extra work.

- Myth #2: Web accessibility only benefits a small minority of users.

- Myth #3: I can worry about accessibility later—I need to get through launch first!

If you’ve ever thought any of the above regarding accessibility compliance, the reality is that these ideas usually come from well-intentioned teams who have not been shown a better way to think about accessibility. When accessibility is treated as a last-minute task, it does become stressful and costly. When it is treated as a core part of planning, design, and development, it becomes far more manageable and far more effective.

With the April WCAG 2.1 Level AA compliance deadline fast approaching, it’s high time to retire these misconceptions and reframe web accessibility as what it truly is: an integrated priority throughout planning, design, and development.

One of the main issues I hear from people just learning about web accessibility is that it is such a large topic that they don’t know where to start. Let’s break it down into three digestible topics:

- What is web accessibility?

- Why does web accessibility matter?

- When should web accessibility be addressed?

What is web accessibility?

Web Accessibility is the art of providing equal access and equal opportunity of web content to people with disabilities. There are laws in place to prevent discrimination against people with disabilities:

- The Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), which prohibits discrimination against people with disabilities and applies to digital experiences as part of doing business.

- Section 508 of the Rehabilitation Act, which requires federal agencies and certain organizations to make their digital content accessible.

- WCAG, the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines, which provide an internationally recognized standard for creating accessible digital experiences.

Types of disabilities

A disability is any condition of the body or mind (impairment) that makes it more difficult for the person with the condition to do certain activities (activity limitation) and interact with the world around them (participation restrictions).

This includes:

- Visible disabilities: can be something physical such as a missing limb, a mobility device like a wheelchair, or other medical aids like glasses, prosthetics, casts, etc.

- Invisible disabilities: mental/neurological, sensory, intellectual or developmental, or invisible health issues, like cancer for example.

- Hidden disabilities: likely invisible but perhaps also hidden because either the individual chooses not to disclose the disability or they themselves are unaware of it, like a missed diagnosis, for example.

Some disabilities are congenital, which means present at birth. Some are acquired later in life. Some are permanent, and some are temporary or situational. (Review the Microsoft Inclusive Design toolkit for several more examples.) At some point, most of us will experience a limitation that affects how we interact with technology. Accessibility is not about “other people.” It is about designing systems that recognize human variability.

Why does web accessibility matter?

People tend to believe that only a small subset of users have disabilities, so they focus on building software to cater to the majority.

But remember, there are 1 billion people with permanent disabilities in our world. If we include temporary or situational impairments as well, that number increases significantly. There are also non-visible disabilities that can affect how someone is able to navigate your website. This data is only from people who report having disabilities., The actual number is probably even greater than we realize.

Reality check: disability is the most intersectional identity—crossing all social, racial, gender, and economic lines.

When you don’t prioritize accessibility:

- People with disabilities in your target audience may be unable to interact with elements on your site, or they may miss important information

- You may miss opportunities to connect with a large number of people, which can be really important—people who you are unable to reach will look elsewhere to get their needs met

- You could face legal consequences if you work in an industry that must comply with Section 508 accessibility requirements (higher ed, government, etc)

We usually think of accessibility as expanding inclusivity. What we don’t realize is that when your site is not accessible, you are exclusionary, potentially leaving out a bunch of people who could be otherwise independent.

Imagine a blind person—they cook for themselves, walk around town by themselves, make purchases by themselves, bathe and feed themselves, etc. Then they go onto your website to buy plane tickets by themselves. They get all the way to the end where they need to input payment information… and the form is not accessible. Now, this completely independent adult person needs to ask someone for help to complete their plane ticket purchase. In this situation, you have actually created disability by removing their ability to be independent.

When you do prioritize accessibility:

Accessibility is a subset of inclusivity. When we build an accessible website, we are building it for people with disabilities but also to improve the overall user experience on your site for all users. Usually, this means that if there is information that’s only consumable by able- bodied users (a video for hearing/sighted users for example), then there is an adaptable alternative for non-able bodied users (a video transcript or captions for hearing-impaired users).

Universal design encompasses both accessibility and inclusivity, without need for adaptations. Consider the below example of shampoo and conditioner bottles: for the pair on the left, the only difference between the two bottles is color. A non-sighted or low-sighted person might struggle to tell which is which. For the pair on the right, however, there are both visual and tactile cues: the bottles are different shapes and have different dispenser types. A non-sighted person could tell them apart by feeling each bottle.

When should web accessibility be addressed?

All too often when building a website, people “save” accessibility for last, thinking they can “edit” their way to compliance in the final run-up to launch. In practice, this approach is costly and often leads to compliance without usability.

A case study by leading digital accessibility company Deque for US Bank found that nearly 67% of accessibility failures actually originate in the design.

Furthermore:

- Trying to fix an accessibility issue during development is around six times more expensive than addressing it during design.

- If you let it get as far as the test environment, it’s around ten times more expensive.

- And if it gets through to production, it’s around 30 times more expensive to fix. (Yikes.)

As remediation costs skyrocket, so does the temptation to cut corners—resulting in a website that technically complies with minimum standards, but falls far short of optimal usability.

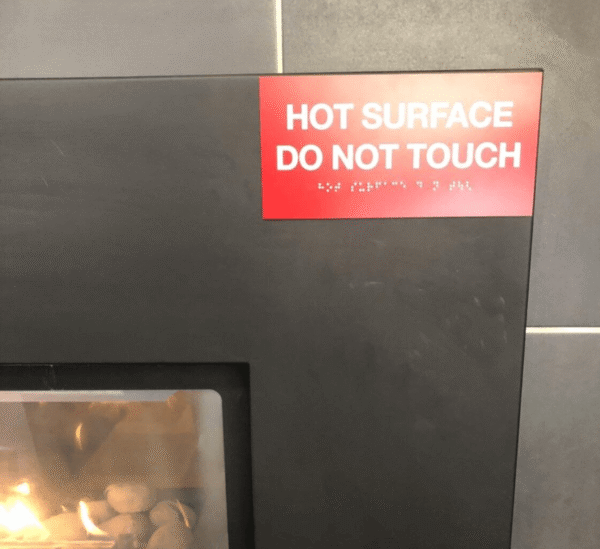

Braille fails illustrate the shortcomings of technical correctness

One of my favorite examples of something being technically correct but completely useless are “Braille fails”—instances in which Braille is included on signage, but in a way that is unsafe or unhelpful for the target audience. Here is an example of a Braille fail: a sign that reads “Hot surface, do not touch” mounted to a fireplace inset. A blind person would have to do the very thing the sign is cautioning against—i.e., touch the hot surface—in order to read it. Oof.

Reality check: Planning for accessibility in the requirements phase and when making your UX and Design plans actually saves resources and results in a far superior final product.

Designing with real users in mind

When you understand the barriers that users with disabilities face, that’s half the battle. Removing the barriers isn’t that difficult. If you are able to, include users with disabilities in your user personas and interviews. Even without technical training, a good start would be to put yourself in the shoes of people with various disabilities and make some small design changes with reasoning.

Motor Disabilities

Imagine that you:

- Can only use your voice to control the computer (such as via Dragon speech recognition software).

- Can move your arm pretty well, but not your hand/fingers. You use some kind of joystick or other adaptive input device as a mouse.

- Have no control of your arms or hands. You use your mouth to control a computer with a stick.

Cognitive Disabilities

Imagine that you have trouble with:

- Memorization

- Use of correct spelling

- Performance of calculations

- Solving of puzzles

Visual Disabilities

Imagine that you:

- Can’t tell certain colors apart—they just look the same.

- Can read, but only at 400% magnification.

- Can’t read, or can’t read comfortably. You use a screen reader instead.

Does your design accommodate these scenarios?

Accessibility as a team sport

Accessibility is most related to Usability. I often think of accessibility experts as “Accessible User Experience Designers”. Even so, being proactive about accessibility isn’t solely the responsibility of the UX/D teams. Everyone has a role to play:

- Engineers should write semantic html and provide keyboard functionality wherever there are interactive components on the site.

- QA professionals should test early and often for each release and make sure to use a screenreader or test keyboard only functionality.

- Usability tests should include users with disabilities when possible.

At each phase in the project life cycle, there are tools for each discipline to incorporate accessibility in what they do. We will break down some of those tools and how-tos in future blog posts.